Cooling Off: Why ‘Main Character Syndrome’ Defies Everything Cool Stands For

Over the past few years, you probably haven’t been able to escape the term ‘main character syndrome’, even if you haven’t been actively online. Of course, everyone has a desire to be the protagonist in their own story; that’s what makes us so individual and unique. And rightly so, future stars who are deemed cool cultivate personas from a young age; they’re not made overnight. When those personalities are nurtured, they tend to go on to do captivating things later in life – think Steph Curry, who grew up surrounded by NBA stars who exemplified coolness in the 1990s. How could he not become cool later in life, when he knew what it looked like having a dad who played in the league?

However, at some point, we began to equate our own inflated ideas of self-perception with coolness and to reduce those who don’t engage with the same elements of culture as non-playing characters (NPCs). If there were ever a need to use the phrase touch grass, it would be here. Few of us ever get to be stars, and even those who are understand that fame can dim faster than it shines.

The gamification of social media presents life as a free-roaming RPG, and it’s not hard to see why. However, what causes tension with the idea of coolness is that the supposed main characters seem to have decided who is cool and who isn’t. If everyone is a main character, what role do the audiences play in deciding what’s cool for themselves?

Social media, loudness and our need to constantly amplify ourselves conflict with this idea of coolness because it leaves little room for mavericks who cause friction with the status quo. If this weren’t the case, we wouldn’t need to post selfies and thirst traps when promoting work, in a bid to game the algorithm. Stars and mavericks don’t play the game; they transcend it.

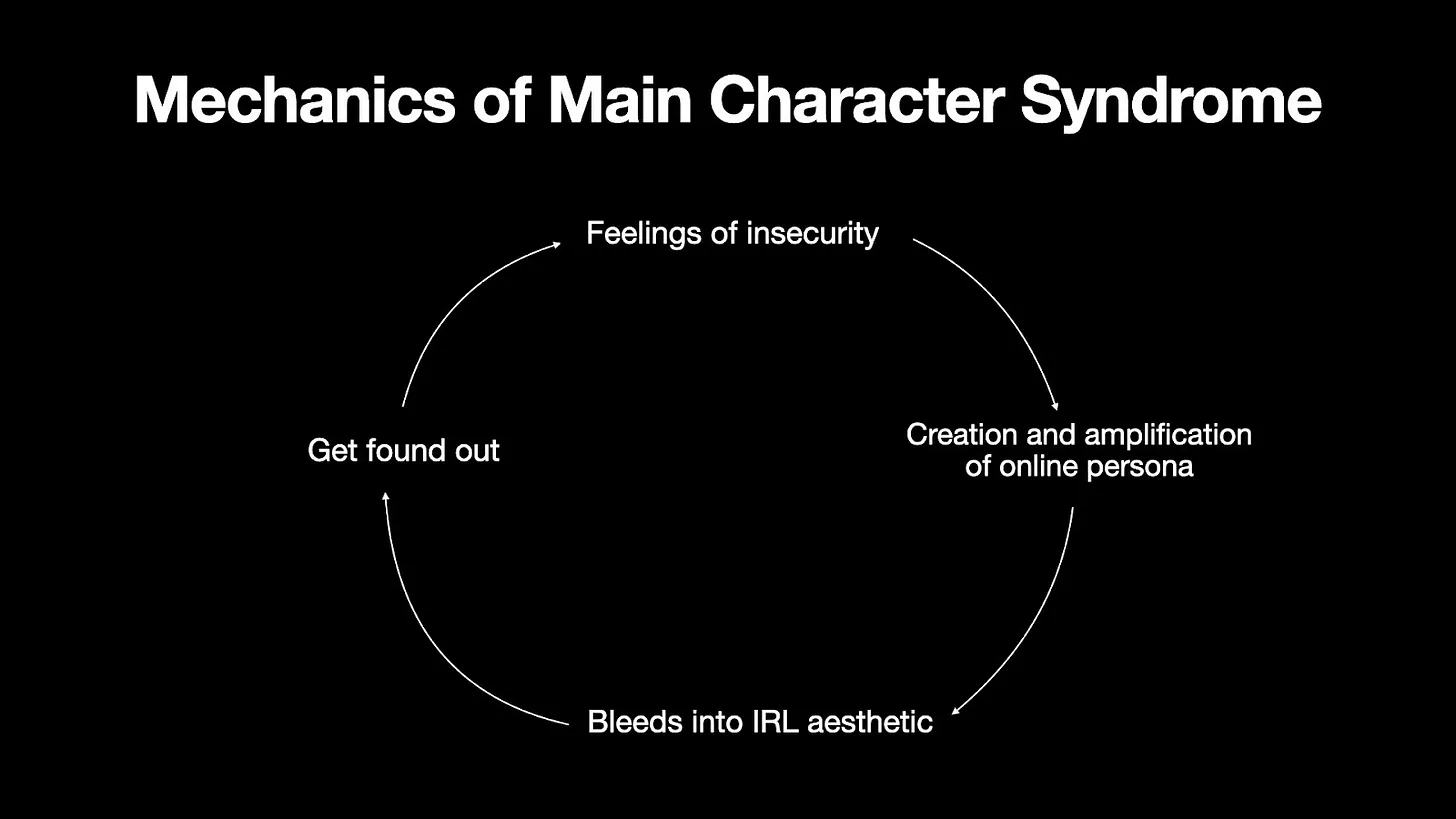

The mechanics of main character syndrome don’t allow space for this because it begins with scarcity or the lack of something substantial. The cool, main character persona has to be built online first in this day and age. Of course, the template has evolved, and many have to fake it until they make it online before they assume the role offline. But the online persona should be an extension of how we move through the physical world; otherwise, there is the danger of being found out by those around us.

Basketball has suffered from this problem as the impending conclusion of Steph Curry and LeBron James’ dominance over the past twenty years looms. The NBA has been scrambling for the next star to carry the baton that Magic Johnson picked up in the early 1980s, closely followed by Michael Jordan. Kobe was ascending just as MJ was bowing out, but in 2026, the Jordan brand has struggled to connect with younger people.

Athletes signed to the Jordan brand, such as Luka Doncic, Jayson Tatum and Russell Westbrook, will always fall under the immense weight and stardom of the brand’s namesake, thus their level of coolness will always be measured against his. And even then, MJ has struggled to be regarded as cool among young people due to the era he rose to stardom; they just can’t connect with his legacy in the same way, not that I think he, as an individual, cares.

That said, MJ’s individuality is what makes him cool to millennials and older generations: MJ refuses to move for anybody, he understands his impact and the fact that people across all generations use his memes, suggesting he’s still a star. Younger people will consider LeBron the greatest on the court based on his numbers alone, but even his staunchest supporters can concede that MJ’s off-court aura is measured by different metrics; LeBron’s by his social impact, and MJ’s by his demeanour.

They are both main characters, stars, the epitome of cool, but the one factor that connects them both is that they’ve left it to the people to decide their coolness. And even in the creator economy, you still need to cultivate an audience to define coolness for you.

Main character syndrome isn’t necessarily a bad thing; it’s a symptom of an economy that extracts labour and energy from people and offers less in return. Social media platforms and tech giants have made it so that attention is rewarded, and ideas of coolness have shifted with that, which is why streamers such as iShowSpeed remain hugely popular among kids across the African diaspora. With far fewer opportunities for young people and rising NEET statistics, why wouldn’t people turn to social media to create new personas that could ultimately lead to them creating new pathways?