Hood Futurism: Remixing the City

We can remix the city by repurposing its design and turning its hostile nature back on itself. Iconic in its legacy, history, and fight for survival, Southbank Skate Space, also known as Undercroft, represents the battle between youth and the establishment as well as public space and how it can be used and repurposed.

SKATEBOARD, an exhibition chronicling the history of skateboard designs since the 1950s, curated by The Design Museum in 2024, focuses specifically on the years since the 1980s, when street skating became popularised and birthed a new subculture. By utilising urban environments and architectural features such as fountains, steps, rails, and curbsides, skaters have consistently found ways to repurpose the city. They are the pioneers of urban futurism. The battle for Southbank Skate Space was finally resolved in 2014 when the Southbank Centre and Long Live Southbank (LLSB) signed a binding deal with Lambeth Council, guaranteeing its long-term future.

Fighting for survival is never enough, though, and often, the real work begins once the battle is won. LLSB needed to ensure that it would remain a cultural beacon and mainstay in the heart of London. The organisation launched a £790,000 joint crowdfunding campaign to restore the skatepark.

London’s borough councils sought to challenge the ‘no ball games’ rule on estates by building cages for football and basketball; however, they’re still few and far between for a country where those are the two most played sports among 11-16 year-olds.

In Rio de Janeiro, public football cages are as common as beaches, and the same can be said for major cities in the USA for basketball. How many artificial football pitches in the UK are free and accessible? This summer, in a joint partnership between Hoopsfix, Basketball England, Haringey Council, Access Sport and clothing brand Half Decent Day, the renovation of the basketball courts in Turnpike Lane was completed. This follows recent renovations at London Fields, New City College and Clapham Common, but there’s a deeper sentiment behind these changes. Purpose-built outdoor spaces encourage participation, not just for seasoned players but also for those who participate. Basketball culture in England, particularly London, has struggled to develop and compete with the rest of Europe, let alone the USA, largely because those spaces have seldom been nurtured.

When you think of hood futurism as a concept, the mind conjures images of Missy Elliott, Busta Rhymes and Kendrick Lamar. However, the deeper you look, traces of hood futurism surface in our daily lives, some more visible and noticeable than others. Traditionally, hood futurism is a concept that merges urban futuristic aesthetics with black contemporary art and performance.

What gave London its cultural gravitational pull to which all underground electronic music seemed to orbit during the 1990s and 2000s has shifted somewhat. In many ways, London has suffered a similar cultural decline to that of Detroit when the USA began importing cars more than it produced them. Writer and musician DeForrest Brown Jr. explores how his hometown’s techno origins in Motown, Detroit, resembled the machinery and metal work of the car manufacturing industry. Techno could only emerge from a modern industrial behemoth like Detroit, with the technology available in the 1980s and 1990s, in the same way London could only produce jungle, UKG and garage in the following decades.

London’s industrial presence has waned significantly and has increasingly become a financial centre and service-based industry, even though that’s also been fading since the late 80s. And all the other factors we explore have all contributed to London’s cultural strength, but despite that, it still ploughs on. London’s music, fashion and creative capital is still the blueprint across the world and on everyone’s moodboards. However, it’s the nostalgia many are buying into, whether they experienced the city at its peak or otherwise.

“That's why wherever I go, I'm flying the Chalkhill flag. And the maddest thing is, if there's someone across the street from me and we're in an unknown third location and they're from Hills, I will know. I can sense it. There's something about my people. Do you know what I mean?” Nabil, an educator and founder of Privatise The Mandem, says.

For many Londoners, the block, estate or more aptly, ‘ends’ has a hypnotic pull on those who live and have ever lived there. Ends is a concept that extends beyond any physical space; it encompasses the meta, psychological, social, political, and, at times, mythical.

There’s a magnetic mysticism that certain areas possess, in some ways it can feel like they’re a portal into another dimension because of the characters, art, culture and way of living they produce. Think Harlem, New Orleans, Brixton, Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro or Compton, for example. One trait each of these areas shares, including Chalkhill Estate, is that they’re historically Black.

“These are real people on the block as well, everything I know is a result of my interactions with my neighbours, it's a village,” Nabil says, “I had to step out of Chalkhill for a bit and I had to see what was on the other side. I just started missing my people. I realised that I felt like I was failing in my responsibilities to the YGs whose older brothers are my friends, and by not being there, my absence felt like I was neglecting my responsibility.” This sense of community and duty isn’t alien and exclusive to Nabil alone.

It’s much easier for Nabil to identify more strongly with North West London than the city in its entirety, especially when it provides resources and local services that often go overlooked elsewhere. “I live on fertile ground; the block has everything you want. You want a bike repairman? I’ve got one. I swear. There's a bike repairman on every block. He does it for free. That's what I mean. This is what we grew up around, where we do things for the love of it.”

Do we need to use TaskRabbit to repair a punctured bike or borrow a ladder because you accidentally locked yourself out, if you’re engaged with your neighbours and know who to call on when one of these instances occurs?

Nabil’s priority and vision are for the local community – his mandem – to become the owners of the land on which they reside. “I'm trying to harness that, which is completely the opposite of what identification actually represents, the condition of gentrification. The precondition for it is the initial displacement of the mandem and my people. And I'm not trying to see them be displaced. That's already happened. So that's happening across the board even today.”

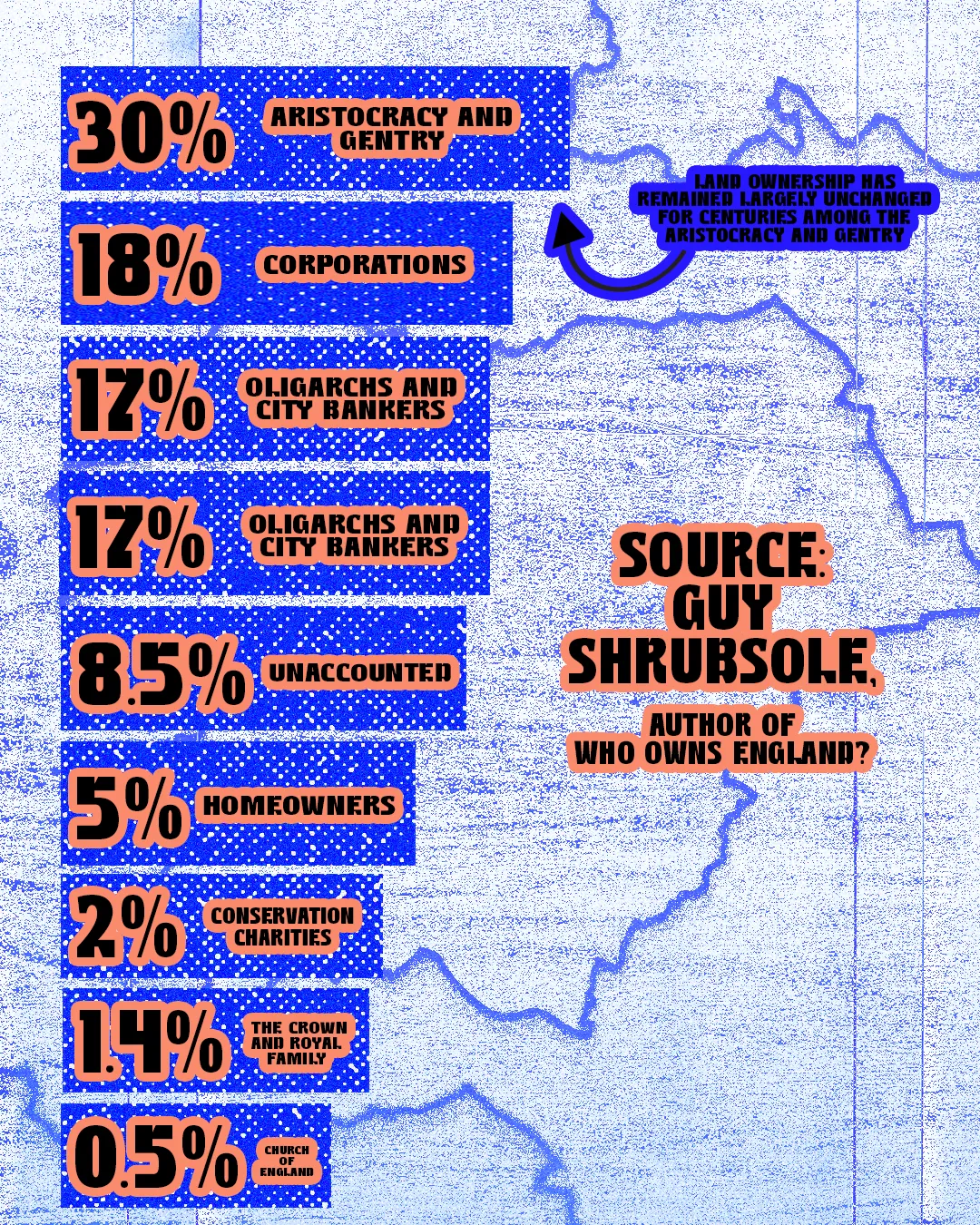

Ownership in a broader sense isn’t just about who owns the deeds and titles to property and land, even though, in the UK, 30% of land is still owned by the landed gentry and aristocracy. Corporations, oligarchs and City bankers own a further 35%. Perhaps what’s surprising is that the public sector owns 8.5% of land, while the Crown only owns 1.4%.

This requires us to think more broadly about ownership and avoid Americanised ideas of what it means for marginalised communities to own land. Zoning laws, gerrymandering and the history of segregation in the United States make it far easier for Black entrepreneurs to own land in their own neighbourhoods, not that that doesn’t come with its own set of challenges.

However, as councils sell off public property such as allotments, youth clubs and estates, Nabil sees this as an opportunity for communities to come together and purchase land. Pardna operates in a similar system, as it allows those within West Indian communities to buy property. This led to a generation of homeowners who previously had no roots within the UK. And this certainly doesn’t mean that we can’t push back and fight against aristocratic and corporate land ownership. “The way they shape the city around them is very much dependent on our erasure. So I'm not trying to feed into that. I don't even want us to get to that point. So I'm like, let's get in early and prevent those decisions from being made. And the only way you can do that is by owning the land,” says Nabil.

Grime wouldn’t exist without the tower blocks from whence they came, and in many ways, it’s the musical manifestation of Nabil’s idea of remixing the city. As grime evolved from jungle, garage, and UK dancehall, young people in the early 2000s began to reshape the music they were creating to fit within the sociopolitical climate of the time. Across the river, Newham and Tower Hamlets-based MCs could see the growth of Canary Wharf, but economically, they couldn’t be further from it.

The meshing and blending of popular sounds in London speaks to the changing landscape of neighbourhoods across the city. You’ll see newly built next to old, whereas in American cities, you’re much more likely to see the complete tearing down of old, replaced by new. Woodberry Downs Estate in Manor House is nearly extinct as redevelopment led to the old estate being torn down in favour of newer developments. My first thought when this happened was, Where did all the old residents go? An uncle of mine (second cousin, really) used to live on the estate up until he left the country, so I have fond memories of the place, particularly as I spent a lot of my childhood all over the borough of Harringey.

What naturally occurs is that the demographic of the neighbourhood begins to change, and then the schools follow. What does that now mean when kids from varying socioeconomic backgrounds and ethnicities are now going to the same schools? What would they be listening to on the playground? More importantly, how does that inspire and inform the music they go on to make? It’s no wonder that when you hear a popular British song these days, you’d struggle to place it in one particular pocket of sound, but rather an amalgamation of multiple. Take So Solid Crew’s ‘21 Seconds’, for example, which was released in 2001 – the group originated from Battersea, and the prominent sound coming out of south London at the time was UKG, which was reflected in the fashion they were wearing in the video. Whereas in 2025, if you were to listen to Pa Salieu and Backroad Gee’s ‘My Family’, you’d find that it’s a cocktail of UK rap, afrobeats and dancehall with neither style more pronounced than the other. This could only occur because of the environments both rappers are in and around.

“I would much rather demand [the mandem] look at how they can reshape the ends to fit their needs through play,” says Nabil, “And one way to do that, I believe, is through remixing because it's something that we do already as a culture. We take the songs of old and we strip it of its components into our favourite parts. And then we take that and we create something new out of it. So I feel like that process can be mirrored in land, not just through sound waves and audio, but through architectural expression. So, cool, we have the ends right now. It was produced by someone else in the past. We can strip it of its main components without displacing us, picking what we like and then remixing the parts that we want to, filling in the gaps to meet our needs.

Nabil seeks to avoid an idealistic approach to meeting the needs of local communities that are under threat of displacement and disillusionment. Because of the way policy, development, and capitalism all play a role in reshaping the city, we find that our needs are adapting to the city, rather than the other way around. A strong example of this would be how Steel Warriors transforms violence into positive community action through the melting down of steel knives into purpose-built outdoor gyms.

“Our needs change over time. So the city is always shifting, and our needs shift with it. And so we have to be able to change the environment to meet our needs as they change over time,” Nabil says, “And so I don't believe in utopias. Utopia, actually, if you look at the etymology of the word, is Greek for no place. It's a place that doesn't exist. It's magical. And as far as I'm concerned, what my work is trying to create are real places that can exist, and they're not sterile places.”

Some of the most imaginative and vibrant cities in the world are incredibly chaotic, where they feel more like Gotham City than Metropolis. The general Western perception that the way people drive in Mumbai and Lagos is chaotic can only derive from a sense that order must be established. If you go to São Paulo’s downtown, there’s an area called ‘Cracklandia’, which feels very much like a scene out of Dark Knight Rises, but still, it’s one of the most popular areas for nightlife in the largest city in South America.

Nabil challenges us to examine what the city can be, rather than what it should be. Of course, cities are centres of commerce, but if you think back to when the largest cities in the world were at their most prominent, they were also centres of communal gathering and the celebration of culture. There’s still room for London to return to this, but in order for this to happen, we may need to be more proactive in how this can be achieved.

“Why would we want to create a sterile, scripted city? That's not life. Life is full of ups and downs. It's full of chaos. So as far as I'm concerned, our cities should reflect the chaotic nature of humanity. People are going to make mistakes. That's fine. Let them make the mistakes. We will learn from them. People are going to do good things, and that's even better. We will learn from those good things and employ it and distribute it across the rest of the city. But we have to let chaos ensue. That's how human civilisation has been from the beginning. So I don't believe in a sterile city. That's what's idealistic to me. It's designing in the natural chaos that humanity is known for.”

For those who crave order and idealism, it may be that urban living is not for them, and rural settings might benefit them more. However, even nature itself can be unpredictable, especially with climate change - a major concern and one of the most pressing issues of our age. And while there is no clear solution to understanding our place in London as it continues to change, there’s no doubt that our future depends on us being agile, resilient and imaginative.