LONG READ: In Our Corner

Rolling with the punches

The first touch is the deepest. My introduction to boxing was built on the foundations of kickboxing in the heart of Leicester City at around 15 years old. A spot behind Burger King meant that the temptation to wolf down a Whopper right after training felt unavoidable after inhaling those aromas throughout each session.

Learning how to defend myself was crucial to my survival out on the streets of Leicester. I grew up in the hood within a community that was constantly under scrutiny. We consistently had to prove our worth and place in society. Being part of the kickboxing community felt like I was protected, whilst also defending myself. I was truly saved by the bell, in more ways than one. People looked like me, I felt fit and found community - a sense of belonging.

Returning to the ring years later in London, this time boxing in its more traditional sense, has provided me with more maturity, depth, and a strength I didn’t know I had. The flow state achieved in every single session has left me craving that dopamine hit. I’m obsessed.

Gathering with misfits trying to make it out feels honest and authentic. Boxing is an environment where I can bring my full self, whatever state or stage I’m at. It’s a feeling of acceptance.

In recent years, boxing has taken a positive turn for women and non-binary people, and this piece explores the whys and hows. It’s been a long and arduous battle to reach this point. Whether it's wanting to reach a place of equality or finding a way in which women are represented in their own right, we will unravel what this means and discover what the future entails for women in the sport.

A Blow-by-Blow history

Women’s boxing is one of those painful coming-of-age stories that began in and out of the ring in 18th-century London. Back then, the streets of London hosted unofficial battles between women. Fights went beyond the ‘typical’ hair-pulling with bare-knuckle fighting, highlighting how women had this physical strength waiting to be released.

The sport went from street scraps to organised competitive fights in 1880, thanks mostly to the formation of the Amateur Boxing Association - but only for men. Champions such as Frank Bruno, Nigel Benn and Anthony Joshua all began their boxing journeys within the ABA and progressed to world title fame.

It took another 116 years for women to be recognised and accepted into a formalised boxing society, hosting non-competitive or exhibition fights. Women were constantly met with resistance in any formal boxing setting.

That was all about to change. In 1996, the legendary fight between Christy Martin and Deidre Gogarty placed women’s boxing on the mainstream circuit. Taking place at MGM’s Grand Garden Arena in Paradise, Nevada, it was part of the undercard for a pay-per-view championship match between Mike Tyson and Frank Bruno with 1.1 million buys.

A testament to the fighters, especially as Gogarty took up the challenge with only 10 days' notice, Martin’s 15 lb weight advantage gave her the win through a unanimous decision after 6 rounds. Ready for anything, Martin and Gogarty were up to the challenge and took women’s boxing into the stratosphere, allowing the sport to be taken more seriously. Public attention boosts popularity and in turn, more investment in the sport.

The living legend that is Nicola Adams, who won GB’s first-ever gold at the 2012 London Olympics, holds a real place in boxing for not just women, but women of colour and queer women. With her win, Adams carried the torch for equality across boxing.

This year’s Olympics in Paris is a clear sign that women’s place in boxing has grown by leaps and bounds since women could finally compete in 2012. At the time, women could fight in three categories: flyweight, lightweight, and middleweight divisions. Twelve years later, the fighting categories have doubled to six in this year's Paris Olympics. This representation has allowed women to compete in more weight classes.

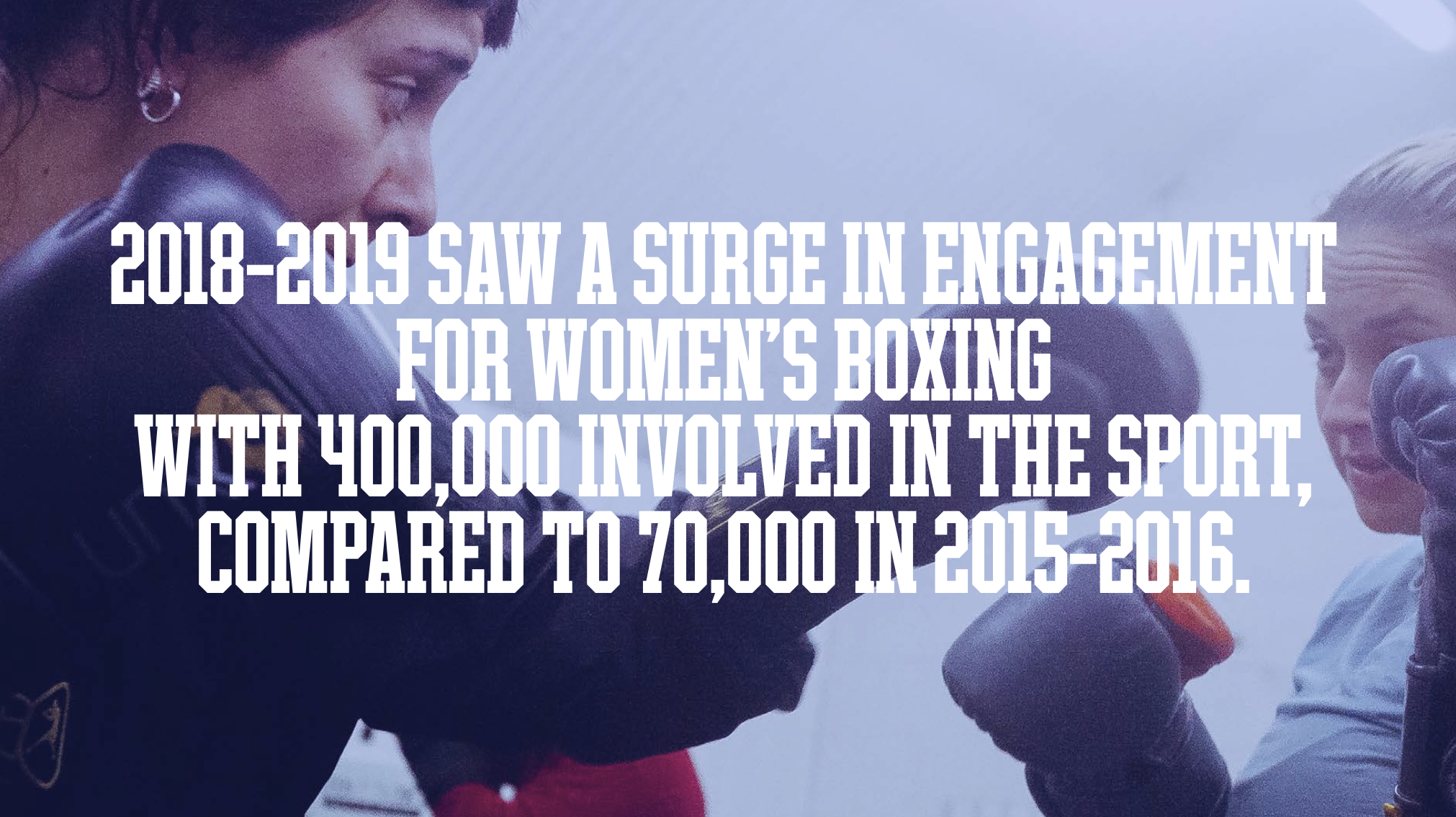

2018-2019 saw a surge of engagement for women’s boxing with 400,000 involved in the sport, compared to 70,000 in 2015-2016 - according to a Sport England survey. For a sport that has become hugely popular within the UK, it’s disappointing to see that it’s not supported in mainstream media - another example of how difficult it is for women to earn their stripes, even when the statistics show the growth.

The quest for equality in women's boxing reflects a broader struggle. Whether it’s equal pay, wider media coverage, increased funding or sponsorship, a level playing field needs to be created for women in the sport. We are experiencing more strength in numbers than has ever been seen before.

Coming out of the shadows

The film Million Dollar Baby captured our attention and then our hearts with a story showing that talent in this sport can be garnered by women as much as men. In the film, Frankie Dunn refuses to train Maggie Fitzgerald because she is a woman. He eventually takes her on after much persuasion and, proving Dunn wrong, she becomes the champion of quick knockouts. It is a shame that the only boxing film that features a female boxer ends in tragedy, unlike films such as Cinderella Man, Southpaw, and Ali, where the male protagonist has an obstacle they eventually overcome.

We spoke with Angelo Bevilacqua, an ex-pro boxer, the owner of Relentless Boxing in London and my trainer who believes “women are getting into boxing because they want to prove something to themselves and the world. Boxing has always been classed as a masculine sport and women are challenging this now more than ever. They are proving they are worthy to fight as much as any man.”

This rings true when looking at the figures. Licenses for women participating in combat sports have risen 51% since 2012, providing a welcome change to the more patriarchal viewpoint of what women can achieve outside of those heavyweight oppressive narratives. WBO, IBF, WBA and WBC are the four major authorities within professional international boxing. Today, you can almost guarantee an equal measure of men and women in each division.

Angelo expresses his sheer enthusiasm, “women actually fit wonderfully in the sport. Caroline Dubois is one of my favourites and Shannon Ryan, the world champion. I follow Dubois because she does the kind of boxing I like, aggressive, heavy-handed and explosive. I want to see more women with all of this potential.”

Safety first

Angelo shares the fundamentals of providing a sense of safety; “you obviously need the right gym to keep you safe. You need a safe environment and you need a safe pairing. That is up to the coach and the gym to provide.”

A boxing gym is subject to people expressing limitless levels of emotion, a term often referred to as “controlled fury” meaning that anger is channelled effectively is indicative of the boxing method. Method Man said it back in 1994, “I came to bring the pain, hardcore from the brain.” This is exactly what happens when exerting all that explosive anger and frustration in boxing, albeit safely.

Speaking to Simone Retief, the third most experienced Boxing Therapist in the world, based in Empire Fighting Chance, Bristol, the first place to introduce boxing as therapy, she advised us that, “anger is normal. Anger is an emotion that you should have. Anger is fantastic. It shows that you've got boundaries. It shows that someone has encroached on your personal space. The difference is the way that we release that anger. But being able to release that in a sporting way and get all those chemical releases that happen from boxing, it's fantastic. It’s safe. It’s healthy.”

Simone courageously shares an intimate story of a member at Empire Fighting Chance; “A woman training with us has experienced quite a few forms of abuse in her life and has never engaged in exercise before. She's always felt very uncomfortable, especially around men. She said, ‘I didn't think that I'd feel safe here, but I do. It feels really unusual. The boxing environment is something I've never experienced before and people just leave you alone. I never thought that I'd feel so comfortable.’ Very powerful what she said.”

More recently, boxing has become a sport that offers a safe space for those who find it difficult to express themselves at home, school, or on the streets, predominantly within working-class and lower socioeconomic environments. The lack of equipment needed to get going helped fuel this - tying your hands with hand wraps is enough to get you by with some shadowboxing. Gloves are not expensive once ready for the pads, bags and sparring. So for little money, the game is yours to contend with. Simone emphasises this by saying “there’s no class divide, all levels are accepted. It's not an expensive sport when you're working out, you're all struggling together.”

Women feeling safe within the sport and being able to express themselves both physically and mentally is a testament to the coaches and the spaces they are creating to channel all of this uncharted talent. Empire Fighting Chance is paramount to introduce boxing as a form of therapy and it’s so popular that there is a waitlist of at least four months.

For more practical safety, brands such as Adidas, Lonsdale, Everlast, Bandax, FLY and Mizuno all have their ways of interpreting protective boxing gear for different socio-economic needs of the market as well as style. BoxRaw is the newest on the block, providing a more fashion-oriented style to the apparel for both men and women, yet still providing the protection needed in training. They have caught the rising trend early but the women’s offering is lacking among the larger, more established brands and it’s time to get involved.

The main event

The lack of broadcast coverage of women’s boxing leaves the sport underexposed and underpaid. Women cannot keep doing this sport for the love of it; there needs to be an effort to retain talent and nurture their futures.

When the pandemic hit, one of the best UK female boxers, Savannah Marshall, was challenged to the brink of destruction at the peak of her career. The 29-year-old from Hartlepool was forced into refunding £30k worth of tickets out of her pocket for her sold-out match against the then-world-leading female boxer Claressa Shields in 2020. Marshall had no backup plan for such a threat, with no promoter or sponsorship to take this hit. A blow to a career which is already so short-lived, purely down to the lack of promotional support offered to female boxers but Marshall continued to fight regardless.

15th October 2022 at the O2 Arena was a moment in history. We saw the first-ever all-female UK boxing card, which featured 11 bouts and 22 female fighters. The most sought-after event in women’s boxing sold out an arena of 20,000 seats. Self-proclaimed ‘GWOAT’ (Greatest Woman of All Time), USA’s Claressa Shields, was joined by arch-rival Savannah Marshall in the middleweight division. This was the fight of the night. They both had everything to lose and everything to gain. The victory went to Shields by unanimous decision. Shields and Marshall reentered the spotlight for the right reasons after the monstrous pandemic blow.

Since then, sports streaming platform DAZN has caught up with the popularity of women’s boxing and is televising at least four women’s boxing matches this March and April, a far cry from 1998 when the British Boxing Board of Control (BBBC) lifted the ban for women to compete in professional boxing. The tables have turned this year with Sky Sports broadcasting women’s boxing along with other women’s sports such as Scottish Women’s Premier League, England Women’s cricket, The Hundred, US Open, WTA Tour, women’s golf Majors, Ladies European Tour, England Netball, Women’s Premier League cricket, F1 Academy and more this year.

Visibility is key to enacting the kind of change women’s boxing needs to gather public appeal and following, much like how the Women’s Super League has been televised mostly on the BBC. For viewership to increase Angelo suggests that “more women need to go and watch boxing. We need women to come together and support women’s boxing. Go down to the arenas, and pay for the pay-per-view. Get the numbers up so women boxers get paid and credited.”

The fact that men and women both participate in boxing should be harnessed as a force for good. This togetherness could pave the way to lessen the patriarchal viewpoint and encourage more equality. Women having less stoppage time than men is still something women are pushing for, Angelo aptly puts “Fans want to see a fight. It’s only fair for women to get the three-minute rounds like the men. Women are training at the same level and as hard as the men. We will soon see more stoppages in women's boxing.” Affirming this kind of levelling up will further determine that women have it in them to compete for the same and further the chances of larger sponsorship and promoters to get behind them.

Outside of boxing, viewership of women’s sports is starting to reach that of men’s levels. Arsenal Women recently sold out their 60,000-seat Emirates Stadium for a game with Man City Women. Football came home when the Lionesses won the Euros in July 2022 and almost came home again when they reached the World Cup final in 2023. Rumours circled about Sarina Wiegman, England’s women’s manager, being poached to become Gareth Southgate’s replacement for the men’s England manager position. A promotion, some might say, but considering the major losses the men’s team have had since 1966, it’s debatable. History maker and record breaker Wiegman has denied the rumours and is staying with the Lionesses.

Women, of course, have different needs and considerations across all sporting spaces, for example, pregnancy and menstrual cycles. The stigma attached to what makes up the natural female physiology has long been rejected. Serena Williams demonstrated that being a mother and the most prolific women’s tennis player of all time is possible. Supporting women through their personal growth and professional development is just as important for those choices to be available. Choosing one path shouldn’t mean you sacrifice the other.

Boosting POC representation within the UK is needed, especially in the public sphere. We’ve seen a raging talent of women come up the ranks:

- Caroline Dubois - the World IBO champion

- Natasha Jonas - the first black female boxing manager

- Mav Akram - a champion of women’s boxing at a grassroots level with her boxing club in Digbeth

- Ramla Ali - a Somali refugee won for her country in the UK and showed that wearing a hijab is acceptable

- Sannah Adam - one of England’s boxing coaches in Bolton

Diversity and inclusion can be at the forefront of mainstream sports and media, demonstrating what this country truly represents but more investment and policy changes are needed. The Sport and Recreational Alliance states that 40% of ethnically diverse boxers have experienced negativity towards them, double that of those who are white. Encouraging POC participation will enable representation to increase. The fight should be based on your skills, not the colour of your skin. There are plenty of POC women ready to take on this battle and win.

Jackie Kallen, a 77-year-old former boxing publicist and manager who was commissioner of the International Female Boxing Association, said recently to CBS News, "They take a beating just like the men. They bleed just like the men, but they don't get paid just like the men." The financial gains are not tallying up to the amount of suffering women are put through.

The main sponsors behind the sport - UNIBET - have received a 12-month investment boost from Kindred Group to support the growth of 3 UK world champions - Raven Chapman, Ellie Scotney, and Nina Hughes. This is the largest deal struck to date in women’s boxing and acts as a callout for promoters and sponsors to get involved. Ultimately, more backing from brands and investors will give space for exceptional female boxers.

The goods to back it up with

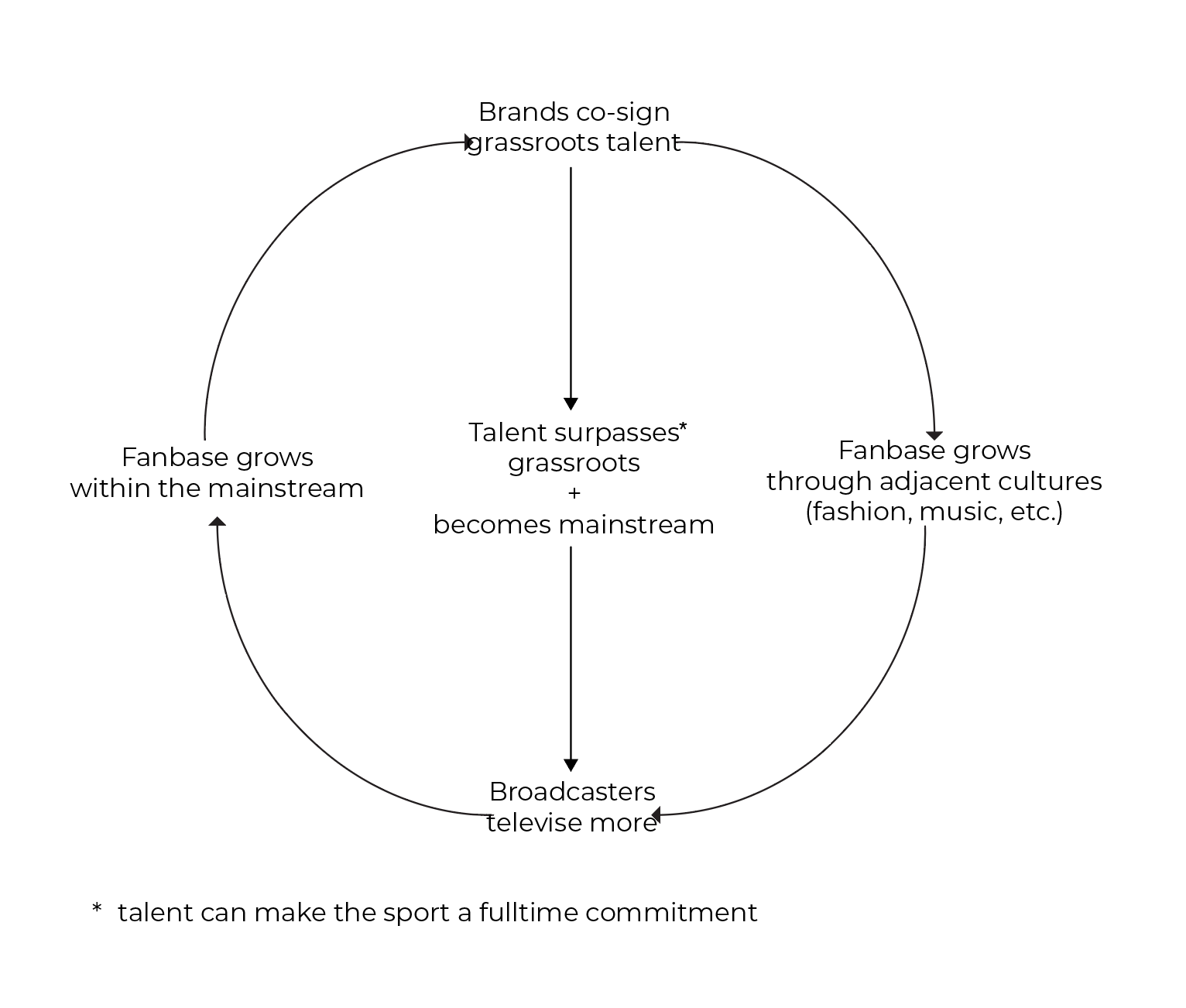

With any kind of sport, visibility and gaining popularity tend to be at the top of the agenda. In turn, this paves the way for brand sponsorship and financial backing as a personality is formed, which the public can get behind. Talent vs popularity is a constant battle for sportspeople to uphold and can often lead to a distraction away from the sport, but it is essential for the longevity of the game. Women’s boxing has a promising future if the balance is struck between the two and funders can get behind the talent first.

Nicola Adams never gave in to this discourse. She let her fighting do the talking, keeping it as authentic as possible with her brazen skills and natural flair for the sport. A couple of TV adverts for E45 and Eastpak, both completely unrelated to boxing, minimally added to the clout she had already created for herself. Adams retained her boxing credibility and integrity whilst still an aspiring figure outside of the sport without compromising one or the other.

Laila Ali and Jacqui Frazier-Lyde are named the “boxing daughters'' for good reason. Ali’s father is the most acclaimed and heavily decorated boxing champion in history, and Frazier-Lyde’s father, Joe Frazier, has allowed for an equally large stir to be made. Laila Ali and Jacqui Frazier-Lyde met back on June 8th 2001. The fight was fittingly nicknamed ‘Ali/Frazier IV’, alluding to a continuation of the famous fight trilogy. After 8 solid rounds, Ali was judged the winner.

In retrospect, the Adidas Impossible is Nothing campaign featuring Laila Ali and her predecessor Muhammad Ali was ahead of its time. We’ve not seen an advert that celebrates women’s boxing since this Adidas campaign in 2004, twenty years ago. In 2022, there were 2,345 women affiliated with England Boxing and with this number rising rapidly, brands could feature their personalities, tactical skills, cultural identities and positions through paid advertisements and share their stories authentically.

Women’s boxing globally is gaining a huge amount of traction; the Asian Games and African Games included plenty of POC women’s boxing, which is not aired widely across the globe, or even at all. Women deserve to take up space in the sport, not just because of the struggle but the sheer talent and force within them.

There can be no more backpedalling. What has happened can’t be unseen or undone, yet there is still much more to offer within women’s boxing. A call to action for brands to be more involved and immersed in a sport that can reach new heights and to be the first to do so.

Fighting for the future

Women’s boxing is on a steep incline towards shaping a more equitable future within the sport. The fight has been brutal and there is a place for infrastructural improvements to suit women’s needs within boxing.

Breaking down the following barriers and looking forward to these solutions will increase the kinds of support and visibility that the sport needs for long-term growth and ambition:

- Women’s boxing needs to appeal to women to watch the sport, not just men.

- For women’s boxing to continue to take off, viewership needs to increase which leads to sponsorship and promotion being essential.

- Further financial support and improved infrastructure are vital for women to build a career out of boxing.

- Women’s boxing should not be purely perceived as a masculine sport. There is a feminine side to boxing that hasn’t been showcased and women should be encouraged to bring their personalities into the ring.

Whether it’s an exhibition fight demonstrating skills, amateur or professional levels of boxing or recreational, there is a place for all levels of interest. The EBF are making their best efforts to make this sport work for all and now it’s up to the brands to follow suit. Key considerations:

Women are nowhere near hanging up their gloves anytime soon. Let’s get us out of the corner and into the centre of the ring. We are worth investing in and the numbers prove it.