Reimagining Cities For Play

Walking around London, we can see multiple different functions of a city at play: London is for work. London is for commerce. London is for education and governance. London is for culture – that most sweeping and overused term – and community, of similar character.

But who dictates how we experience culture and community in London and what culture and community we are allowed to experience? In recent years, there has been discourse around the erosion of certain elements of culture and communities in London, most notably through the frequent closure of grassroots venues and the rise of gentrification.

But this is not a(nother) piece on either of those subjects, as vital as they are. This is a piece about how we might counteract the erosion of community and culture by reimagining cities as a space for play. And I don’t mean the kind of play that can be architecturally designed into sterile development plans, with designated communal areas for social cohesion and perfectly manicured gardens to help us interact with nature. How can we reinterpret the existing concrete city as a space for recreation?

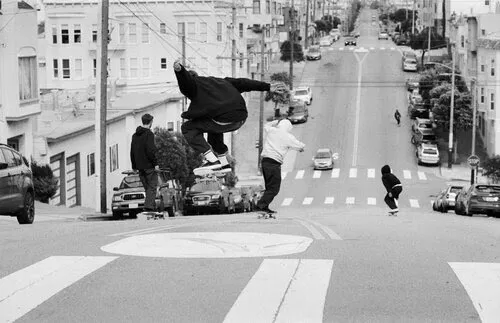

A good example of this happening in real time can be found within skateboarding and graffiti communities, where both subcultures challenge accepted notions of what a city is by reinterpreting its infrastructure in ways that benefit pleasure as opposed to the intended function. While skaters transform curbs, ramps and handrails into instruments from which to perform tricks off, graffiti writers see train carriages, bridges and otherwise empty brick walls as a canvas on which to express their creativity.

Through doing so, skaters and writers disrupt the economic and functional logic of a city by prioritising that most human of instincts: play. Where others play where they are supposed to, they see their whole city as a playground. Although not all play looks the same, there is certainly something to be learnt from this interpretive and imaginative attitude towards cities. How can we repurpose existing space in ways that prioritise play?

The non-profit arts organisation SET is setting the standard (excuse the pun) already by turning disused buildings (such as a Victorian pub, a book-packing warehouse, a Grade II listed train station and several high-rise office buildings) into event spaces and affordable artist studios. Working under similar principles to a guardianship, SET occupies vacant properties via a temporary rent-free lease, agreeing to cover business rates, utility bills, building insurance, ground rent and service charge. While there, SET hosts exhibitions, talks, screenings, club nights, live music events, workshops, dinners, and runs a cheap bar and cafe.

Occupying disused buildings to throw parties in isn’t exactly a novel idea. For years, people have found ways to rig sound systems in empty warehouses and discreet railway arches at unlicensed squat parties. SET have simply found a more legal way of doing this.

Conceptually, illegal raves provide interesting insight into the narrow mindsets with which we currently view our cities. While an architect might be praised and awarded for converting an abandoned space into a block of flats, there is no grace for those who convert abandoned spaces into temporary music venues, all in the matter of a night. This is, of course, because the latter entails trespassing on property that does not belong to the ravers. But what if we were to rethink the way we view our cities? Who does this city belong to? Who should this city serve? The hands of a few select property developers, or those who actually live here?

Squat parties tap into the very essence of play – pleasure for pleasure’s sake. They highlight its rebellious nature – that childish instinct to go where we are told not to, and do what we are told not to do. When we look back at the history of raves, we see how play can bring people together, fostering a sense of community, freedom and inclusion. We see how play has shaped creativity and art, birthing new genres of music and sparking ideas. And we see how play has been stifled time and again, framed in negative terms, and pushed further to the edges of society. This is the power of play; governments fear what might happen when people play too much.

Community ownership also offers an effective path to reframing our cities around play. Recently, in Hackney, a group of residents and charities launched a legal application to take over the now-defunct Colvestone Primary (a school I grew up competing against in cross-country running). Under the Localism Act of 2011, once buildings are listed as ‘assets of community value’ with the local authority, the community has a right to bid for the property if the council decides to sell it.

While a dire reflection on the state of Hackney’s extreme gentrification (which has led to many of its primary schools closing down because young families can’t afford to live there anymore), the bid also provides a positive model of how communities can come together to prevent private developers from buying up property to turn into more unaffordable housing. If granted, the proposed plans will see the listed Victorian building transformed into an “educational, cultural and social hub”, offering lessons in music, art and design to young people.

Without private investors involved, the acquired asset’s usage and benefits are directed towards the needs and priorities of local people, which generally fall closer to play, not for profit. Other similar projects worth mentioning include one in Lewisham, where the female-run radio station Sister Midnight has gained the rights to turn a former Working Men’s Club into the borough’s first-ever community-owned music venue.

Like other community-owned music venues around the country (such as Wharf Chambers in Leeds), anyone can buy a share of the venue and become a member of its co-op. This money feeds directly into the business (which currently means funding the building’s refurbishment), while investors will also become the legal owners of the venue and be involved in all democratic decisions regarding its management.

Paradoxically, public space can also be managed in this way. With so much of London’s “public space” actually owned and controlled by corporations, developers and private backers, community involvement in the use of common areas is an effective way to prevent what The Guardian has named “the insidious creep of pseudo-public space”.

Gillett Square in Dalston, for example, is managed and maintained by Hackney Co-operative Developments (HCD), a local community development agency with membership open to all those who subscribe to its goals and values. While the square itself is technically public, the co-op has been in control of its bordering commercial premises since the late 1990s, preventing the area from being gentrified by a profit-hungry developer.

HCD supports businesses such as Kaffa Coffee, The Vortex Jazz Club, Chicago Barbers and Ewarts Jerk, and runs an ongoing cultural programme in the space that includes art exhibitions such as Hackney Art Activism Festival and events such as NTS Square Party, Kaffa Live, Haile Selassie Irie Earthstrong Celebration and a SkatePal fundraiser raising money to build a skate park in Palestine.

Aside from commerce, music and art, Gillett Square is also a key social hub for residents, skaters and passers-by. Multi-functional, it provides an imaginative solution to maximising our urban spaces. Similarly, venues such as Reference Point, The BBE Store and The Barbican, which recently converted its car park into a temporary club, exemplify the versatility of the city’s physical spaces.

Ultimately, it is about reframing how we perceive the purpose of a city. Using our resourcefulness and creativity to see its intended function in new and playful ways: transforming a disused railway line into a garden allotment, an empty pavement into outdoor seating or a shipping container into a radio station. By prioritising play higher up the city’s agenda, we can start to create spaces that benefit a broader segment of society.

But people must be open-minded to this change in narrative. If you live next to a club and it’s noisy, then you have no leg to stand on complaining about the volume; that’s just London providing its function. London is also for play.