The Slow Revolution

Without sounding too dramatic, the human obsession with speed is a cultural phenomenon that stretches back to the dawn of civilisation. We have always been on a mission to make things faster. From the invention of the wheel to the industrial revolution to the replacement of takeaway leaflets for Deliveroo. Innovation, under capitalism, is largely defined by our ability to make life easier, and this often means faster. When Steve Jobs invented the iPhone, he brought the internet to our fingertips, giving us faster access to clothes, cabs, dates, news, TV, music and friends than we ever had before.

In essence, we live in a culture that celebrates shortcuts. And that’s understandable. The less time we spend on tedious tasks such as food shopping, the more time we can spend doing fun activities. In fact, taking shortcuts in life is actually an evolutionary skill. For early hunter-gatherers, food was scarce and therefore energy was precious; saving it could be the difference between life and death – particularly if a storm hit or a predator appeared. But we are no longer hunter-gatherers. Society has evolved drastically, and yet our inclination to preserve energy or cut corners has remained, and thus modern technology is designed to increase productivity and reduce manual labour.

Arguably, the most extreme manifestation of our obsession with speed is the rise of short-form content. Since TikTok launched in 2016, media and entertainment have become progressively faster. For those who use the app, gratification is expected to arrive within the first few seconds of the clip. It’s called the ‘three-second rule’, promoted by creators who claim they can help you #makemoneyonline. The fact that we expect a video to entertain us in the span of a TikTok, Instagram Reel or YouTube Short says a lot about our attention spans.

And it is impacting other forms of media. Songs are being structured so that the catchiest part comes around sooner, and TV scripts are becoming faster-paced so as not to lose their audience. It’s as if we have lost all sense of patience. When we Google something today, we are provided with a condensed AI Overview of information from “multiple relevant and reliable web sources”.

But sometimes you can’t shortcut information and entertainment. Sometimes it is necessary to watch a film entirely or read an article from top to bottom to understand its full meaning. To compress is to lose nuance. These examples are obvious. But what if we apply the same logic to other shortcuts? What depth of meaning do we lose when we order a takeaway online as opposed to meeting our local restaurant owner?

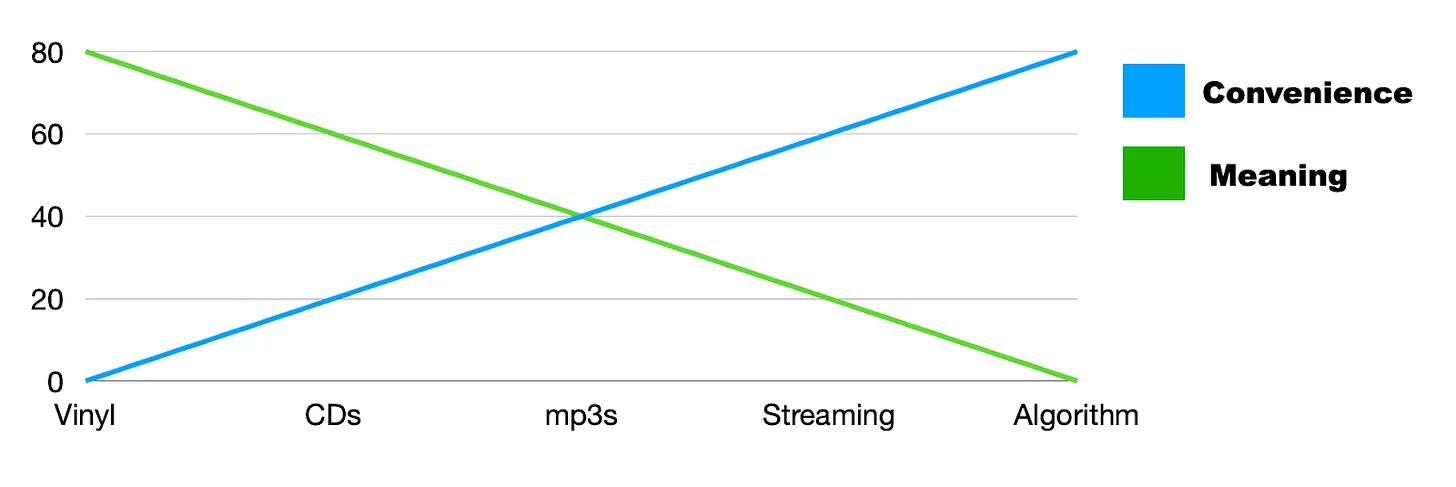

Convenience collapses the process. It cuts out the steps needed in order to achieve an outcome. Take, for example, music. Music consumption has changed exponentially over the past forty years, from vinyl records to CDs to MP3s to music streaming services. This evolution reflects an increase in convenience. We no longer have to visit a record shop to buy music and place it carefully on a turntable to listen. In fact, we no longer have to select our music; we have algorithmically-generated playlists that do that for us.

When you look up the word ‘inconvenience’ in the thesaurus, you are presented with a selection of negatively-associated words. ‘Trouble’, ‘bother’, ‘nuisance’, ‘hassle’ and ‘annoyance’ all point to our societal aversion to doing work. But what if there is meaning in the process of digging, selecting and buying a record? What if there is value in these intermediary steps? The more time and effort we spend actively engaged with something, the more impact it will have on our lives and the deeper the connection we build with it. By increasing productivity and reducing manual labour, we can collapse this process. And when we collapse this process, we collapse meaning. If this were put into a graph, it might look something like this:

A similar process has happened with trend cycles. Where previously eras were defined by distinct fashion aesthetics, collective mindsets and music genres, now there is a new idea every season, if not month, as culture churns out more than it can handle in a dizzying spiral of TikTok videos, Netflix series and fast fashion. The speed at which these changes are happening ultimately reduces their impact. How much meaning can you have if you are only in vogue for a week?

But it is from within this dizzying spiral that we are starting to see the early signs of rebellion, largely led by members of Gen Z. This is happening across the cultural spectrum, spawned in the crevices of Reddit, YouTube and TikTok and spreading outwards. You might call it: The Slow Revolution. A push-back against the speed and convenience of modern life, in favour of depth, process, and meaning.

We see it in the Gen Z iPod renaissance, where young people are harking back to a time when music acquisition was far less streamlined. When music files had to be downloaded, uploaded and listened to repeatedly because the selection on your iPod was ultimately finite. Instead of seeing this procedure as a ‘nuisance’ (as you might expect from a generation born into the age of convenience), many are seeing it as a novel experience, and one that allows for a more sustained and meaningful attachment to their music.

They understand that the process put into this type of listening and the limited choice it entails creates deeper bonds with each artist, each track, and encourages a more active ear than one might otherwise use when being suggested songs by Spotify. Where smartphones and music streaming have made our music experiences gradually faster, the use of MP3s and pirating sites has reverted to a more drawn-out process. Each step requires your full attention and intentional work, giving you a greater appreciation for the song when it’s finally playing through your earbuds.

Other micro-trends in 2025 signalled a desire to slow down. In August 2025, The Guardian reported that young people are ‘flocking’ to independent cinemas, drawn in by the promise of a ‘no-distractions’ zone. The words ‘I almost forgot the whole point’ could be seen plastered over TikTok videos with the song ‘Take My Hand’ by Matt Berry playing in the background. The intention behind it? To remind users to take a step back and reflect on the small joys of life, the little things, like taking a walk in the park or having tea with a friend. It was about slowing down and remembering to appreciate the simple, meaningful moments that are so often overlooked amidst the chaos.

Then, in March, Al Jazeera posed the question: “Are Gen Z rejecting city life for farm life?” According to the media outlet, a small group of young people are giving up fast, digitalised urban ways of living and turning to a lifestyle focused on self-sufficiency and sustainability. This involves growing their own food and even producing their own clothes with natural materials. Here, again, we see a return to analogue methods that allow time, attention and process.

This reversion to analogue processes represents a shift away from the industrial and technological revolutions by lowering productivity and increasing manual labour. It takes us back in time to when you had to physically make things. If you wanted butter, you had to churn the milk. If you wanted a chair, you had to carve the wood. If you wanted a new dress, you had to thread the needle. It replaces convenience with work in contradiction to our modern-day understanding of progress, the thinking being that, actually, in these drawn-out, methodological processes, we might find greater appreciation for the product at the end.

While these are small pockets of the generation, so often these micro-trends are at the forefront of new developments, leading the way in a particular field. Eventually, they spiral upwards and hit that mainstream, forcing a turn in the tide as the masses catch on to new (or in this case, old) ways of doing things.

Will 2026 see a return of the analogue? Will we see more people walking to their local takeaway shop? Taking the night bus home? Will we see an even greater rejection of online dating apps in preference for in-person events? Print media is already making a comeback. How is this going to shape how we consume content moving forward? Will short-form entertainment get longer, again? Will Gen Z start to write letters? Ultimately, will we see a digital burnout so great that Gen Z will long to engage with the physical world?

And how can brands respond if this happens? What will the strategy be in a world that’s shifting towards slower and meaningful consumption? Perhaps they need to start building experiences that are human-centred and tangible, even if that means clunkier and less streamlined processes. People are aware that value does not necessarily come from how fast or how easily a service can be provided. In fact, they have seen and lived the adverse effects that these qualities can have on products. As we enter 2026 and beyond, will people start to value brands on their ability to create meaning and not convenience?

What might this look like? How should, for example, music streaming platforms respond if the slow listening movement expands? Should they strip it back and keep it simple, without superfluous, AI-generated content that only makes our experience less human? How can they find ways to deepen fandom and reignite the connection between music and its fans? Can artists personalise their own Spotify pages? What if there were an optional setting that prevented us from skipping through, or past, songs, encouraging the listening of tracks and albums in full and creating a deeper attachment to artists?

Meanwhile, brands that attempt to “target Gen Z” through short-form advertising content might have to rework their game plan going forward. For sure, you will grab our attention and hold it for a matter of three seconds, but will you make a lasting impression? Will we be thinking about the campaign days later, pondering on its meaning and noticing things we hadn’t before?

If we see a push back against speed and convenience in the coming years, brands will need to react by centring emotion, nuance and depth. The slow revolution is still very much at the edge of culture, with big tech making billions off of our addictions. But, as we all become increasingly aware of this, the cry for something different will only get louder. Brands that respond to these cries by providing healthier alternatives will win. And brands that cave into humanity’s worst inclinations risk losing their integrity.

This means making work that evokes curiosity. Work that challenges its audience by allowing stories to be told without compression. This means the stories that sit at the heart of the brand, as well as those of their campaigns; give both time, space and context to unfold. Embracing this shift means understanding the underlying forces and deeper significance behind it, and tapping into the shared emotions that drive consumer behaviour.

Five ways to slow down in 2026

- Listen to albums the whole way through

- Select the ‘web’ filter on Google to switch off AI Overview

- Organise work meetings in person, not on Zoom

- Take the night bus home in numbers

- Walk to your local takeaway restaurant