What do the alien movies of today say about us?

Aliens are taking over our screens this Christmas. They are on our TVs, in our cinemas and cropping up in popular discourse across social media, in group chats and in the ON ROAD office. A horror trope that has featured in science fiction plots since 1902, aliens have been front and centre of Apple TV’s latest hit series, Pluribus, as well as Yorgos Lanthimos’ recent feature film, Bugonia.

In the former, an extraterrestrial signal creates a virus that sparks a global phenomenon called ‘The Joining’, which turns all but a dozen humans into one mind — memories, knowledge, and emotions are instantly shared among everyone, allowing them to act in sync with one another. Meanwhile, Bugonia tells the story of Teddy, a disgruntled tinfoil hat-wearing beekeeper who captures the CEO of a major pharmaceutical company in the belief that she is an alien.

By using the trope, both become part of a long lineage of psycho-analysis that investigates the existence of alien conspiracies, stories and sightings in society, and what they tell us about the times we live in. For Carl Jung (writing in 1958), extraterrestrial encounters were a “modern myth” reflecting collective anxieties during the Cold War. They were a projection of our darkest shadow during a time of global tension; our worst traits cast into an external, unknown enemy.

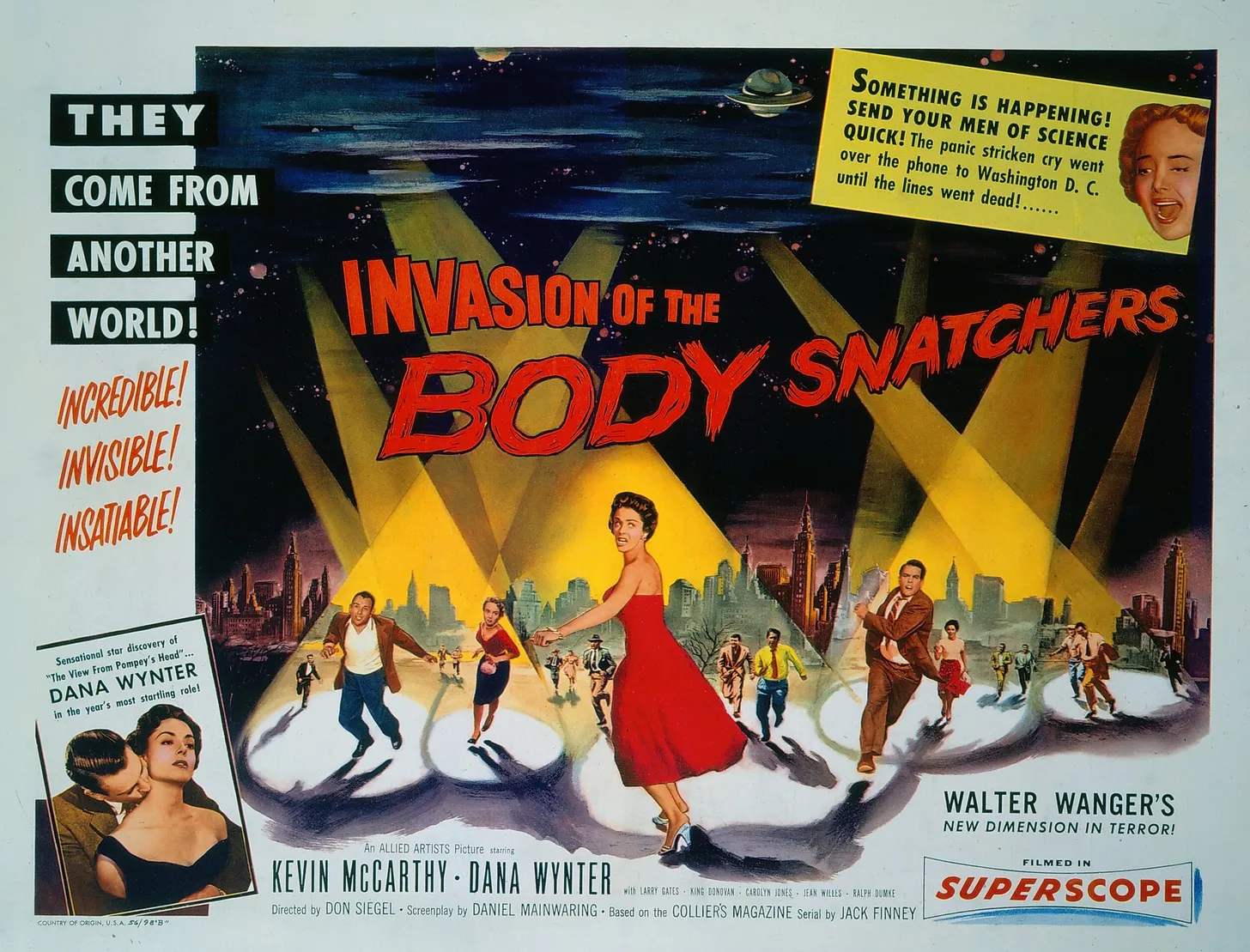

Around this time, films like Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), Village of the Damned (1960) and Planet of the Apes (1968) were released, depicting evil non-human creatures that want to conquer and enslave us or hijack our minds and bodies. On the whole, science fiction films during the Cold War era presented aliens as frightening, evil and deadly.

By the time we reached the 70s and 80s however, a shift started to take place in the sci-fi genre. Released just after the Vietnam War ended, Aliens (1979) complicated the standard formula (aliens are bad and want to take over + humans must defend themselves), by critiquing the immorality of its human characters in venturing into space and symbolically highlighting the devastating impact of colonisation. Likewise Star Wars (first released in 1977) explores similar themes, exposing inherently corrupt power structures and their legacy of oppression.

But that’s where Bugonia and Pluribus differ. In these two modern evolutions of the genre, the standard formula is once again flipped, but this time in an even more dramatic critique. Here, the existence of aliens is not only used to call into question humanity’s own malaise, but to suggest that we are in fact so hopeless that we actually need extraterrestrial species to save us from ourselves.

In Bugonia, in a dramatic plot twist at the end, we find out that Teddy, the unhinged and violent beekeeper, is in fact right: Michelle Fuller is in fact an alien and does communicate with her spaceship via her hair (Teddy was right to cut it all off). But, what Teddy was wrong about, is that Michelle’s alien species are not on earth to destroy us, but to save us from our own self-destructive tendencies. The joke is very much on the audience.

Less straightforward but equally critical, the plot of Pluribus also poses questions about humanity’s need for salvation. While the hive mind that has been forced upon us by aliens eradicates all sense of individuality and free will, the result is that we are all happy, and there is no suffering nor inequality. Perhaps a small price to pay for world peace. The debate that is aroused is the classic ‘greatest good for the greatest number’ argument, which, in the context of the show, would suggest a united consciousness is actually a good thing for humans – as many in the show do believe, aside from the privileged American main character.

What does it say about our collective anxieties of today that our alien fables suggest we actually need aliens to rescue us from our own evils? That our world has become so absurd, so violent, so unstable, that we need something external to put us right again? These are the questions The Matrix trilogy sought to answer, with the main characters seeking freedom from the world that they knew. It’s one of the reasons why the original film has endured, particularly as it speaks to the digital and physical worlds we now live in.

In his book The Same Villains as Always: A Theory of Conspiracy Theories, the philosopher and cultural critic Pepe Tesoro attributes the rise of complicated alien stories in the modern day to our sense of growing isolation:

“This enormous technological acceleration and political instability, figures like Elon Musk or Peter Thiel, companies like Palantir, the climate crisis, and the genocide in Gaza have brought back to our imagination the darker side of technological progress. It’s natural that alien fables are making a comeback, but the human species is no longer portrayed as a heroic, unified collective subject worth saving. It’s not even the handsome and competent investigator, like Fox Mulder in ‘The X-Files’, who confronts the alien. Today, the individual is depicted as simply alone, distraught, and abandoned.”

But perhaps there is a moral we can find in both narratives. If hive minds form the central plot device in Pluribus, then a similar idea is being hinted at in Bugonia. Named after an ancient Greek belief that bees can spontaneously generate from the carcass of a dead cow, Begonia is filled with bee symbolism – bees of course being the most obvious example of a hive mind at work in real life (and, of course, the phenomenon’s namesake). In other words, both stories point to the need for humanity to work together (like the bees) in a system of collective care and survival; looking out for one another, co-operating and acting for the benefit of the whole and not the individual.

The by-product of capitalism is individualism, and collectivism counters this economic principle and structure. Perhaps, both shows are asking us to delve deeper beyond the idea of the hive mind and look to a world where collectivism is at the heart of society?

But the hive mind motif also raises questions around social media, AI and their potential to flatten originality and inhibit individual thought. If we sacrifice our consciousness to the collective and there is no friction or authenticity, is there really any point? What do we lose at the expense of perceived happiness? Once again the sci-fi genre has been updated for our times, used to express our collective anxieties and sharpened to interrogate humanity’s deepest insecurities, without ever fully presenting an answer.